Hannah Saltmarsh

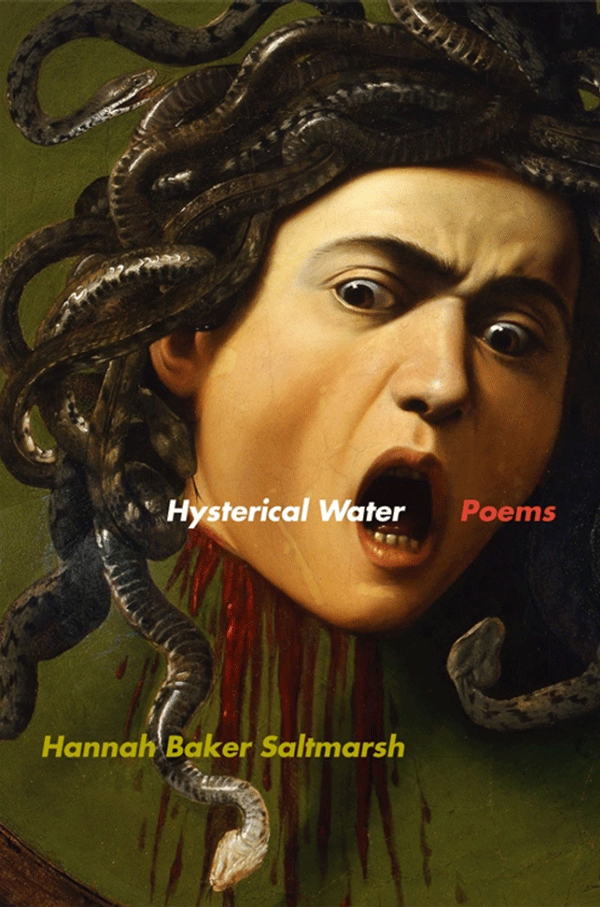

Hannah Baker Saltmarsh is the author of the poetry collection, Hysterical Water (University of Georgia Press, 2021), an assistant professor of English at Mount Mercy University in Iowa, and a mother of three. She is currently working on a second book of poems about environmental disaster; and a critical book about the poetics of motherhood. She is influenced by and crazy about so many 20th and 21st century poets and writers, particularly Alicia Ostriker, Adrienne Rich, Claudia Rankine, Natalie Diaz, Frank Bidart, Javier Zamora, Thom Gunn, James Baldwin, Elizabeth Hardwick, Grace Paley, Joy Harjo, Toi Derricotte, and Toni Morrison, among others.

Her submission to “Among the Unrest” includes two poems, “Digging in My Grandfather’s Garden” and “Jude Wept.” that explore grief and loss during the COVID-19 pandemic, and the importance of art as a form of healing and connection. The poems are elegies for the two people that died in Hannah’s life - a young person who committed suicide and her nearly 100 year old grandfather.

Digging in My Grandfather’s Garden

Tragic fury rose out of the ordinary morning from your car’s exhaust pipe—

why didn’t you turn your neck to the left, near the lilac bushes,

just to 9 o’clock, or look in the rearview mirror

a second to see the red van before plunging into it?

In the 50s, no one had car seats. After the collision,

your unbuckled child’s brain began to seize

with electrical storms. From then until his death, your son wore

an epileptic chain-link bracelet. What about your own heart?

You condemned yourself on daily long walks

for storming in reverse, blindly, in your station wagon out of

the driveway. Nothing comprised forgiveness. Your repressed anger

grew monstrous talons four-horizons deep into the subsoil.

When you came back from the dead, in your 80s,

leg veins in your heart, you wept for your lost child,

held a blanket, crying over your anger or call it self-pity—

that machete vandalizing an organ piano you loved to play.

I only saw your rage once, when I opened the earth in your garden,

plucked out three or four tulip bulbs, carried them into your house.

Did I even come up to your belt buckle? Swaddled my babies,

my Potato Heads. In the earth, all that time, they were there

secretly like when I found out the moon was there all along,

during the day, a craggy thing of invisibility, whirling, satelliting

around its parent, flung in the sky. My flowers! My flowers!

The emerald on your finger I thought would hit me,

though it didn’t. Who had we killed? The grass, the beautiful uncut hair

of graves, caressing the shoulder blades of our dead.

I asked my father in the dark of bedside prayers about his dead brother.

Relieved my uncle, if he were alive, would live with us,

I couldn’t comprehend that he wouldn’t make more than fifty cents

an hour for connecting wires, that he wouldn’t connect to dreams, wife,

home. I’d marry him! I wouldn’t care he couldn’t do

those things! I thought I’d solved everything. My father’s eyes

enormous as those bulbs, muddy with tears. Tulip bulbs small

as hermit crabs--if you pry the dead red claws and shoelace knot eyes

and crescent gut from the shell, place the shell back in the cage,

the mourner, sibling-less, will inhabit it, a mercy.

Jude Wept.

The last thing you did with our kids—how to trace their hands,

cut out the wing shapes of fanned apart fingers, for exultant angels.

This is not metaphor. The angel is the angel,

the last thing is the last, period.

You loved and laughed at the things my children made.

What you made last was the undoing of

your own nineteen-year-old body

in a cocktail of who-even-fucking-cares?

Your given name flung open without your consent

in the obituary. Left for a friend’s awful discovery,

the last word you wrote was change, the language of

demand—why did you wager for resistance

with your own colorful sweatshirted youth?

When you wrote the letter, you still had your faith but

what was it? More often I think god weeps with me.

The shortest sentence inside the leather,

Jesus wept. The fullness, maybe no one knows enough.

One of your Sunday School flock thought you, like god,

aren’t boy or girl. I like the story, but why does queerness

have to be supernatural now to be natural?

A queer lens of god I like, inching us further from patriarchy, homophobia,

repression, transphobia, self-flagellation, hatred. In the pews,

you turned back, every few minutes in worship, towards my baby,

who understood also the squirmy, floaty

effervescence of your greeting. Your blue stalks of hair

sprouting out of the blonde, the spirographs of your glasses and your

gape, the whispered trill of your baby talk made it seem like your presence

was the surprise of an easter egg

upright in the churchyard gutter on the hill. Perched on the 70s

basement couch, a surrealist sunrise over woodsy mountains.

I just want to remember you in your you-ness,

not the historic complicity of faith

in the short lives of queer youth, flashbacks of

my brother’s suicide attempts. When Rev. Lenny wrote, The church

is queer, folks, has always been, the usual envelopes came back,

stamped, return to sender, undeliverable.

I think of my daughter when she was feverish with flu,

having vomited, telling the bathroom mirror, It’s a new day.

Sometimes, the sickness doesn’t leave. My daughter made a mountainscape

for you with her quietest voice, You’re so far away.

My son built binoculars and a spyglass. Outside, icicle hands

fanning out from cornices. Invisible old leaves, hurricane debris cleave

together in the frozen throats of gutters. Askance shovels stick out

of the snow as if the sky were trying to bury us.